Fastest Known Time for Peter Huggett on Fehmarnumrundung

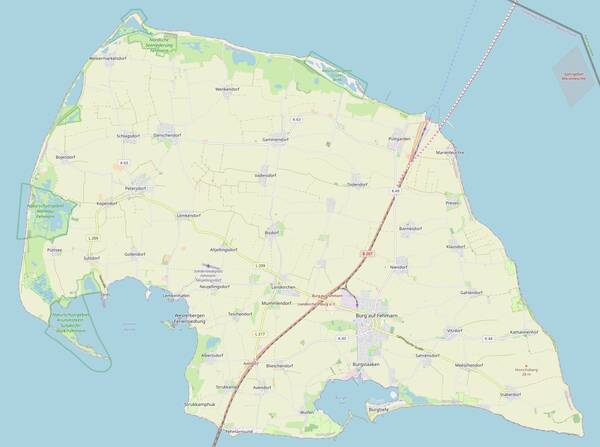

The island of Fehmarn is Germany’s third largest one with an area of 185 km². It’s known for having a sunny sub-climate and therefore it’s a popular holiday destination for Germans in the Baltic Sea, easily reachable via a bridge.

During the summer of 2021, the extended family and I were fortunate to spend a week’s holiday on Fehmarn, enjoying the peace and quiet of the place and the noise of our kids at the same time. We liked it so much we decided to do it again this year, in 2022.

In the meantime, I got the idea of running the perimeter of the island. Around the whole of Fehmarn on the outer most accessible routes, which is about 68 kilometers. Many people have certainly already done this, but according to the fastestknowntime.com stats, the current best is at just 6:33 hours, which I thought would be possible for me to beat.

Then, a few weeks before the holiday, another thing happened. Unfortunately, my father-in-law Peter Huggett died at the age of just 75 after battling the terrible disease of ALS for about two years.

I looked up to him and have learned many things from him over the years I’ve known him. He was full of energy and an exceptionally curious person with interests in many areas. Born in Loughborough, England, he and his family migrated to Johannesburg, South Africa when he was three years old. He then spent a few years with them in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and came to Germany as an English teacher at age 26. He was an avid cyclist, taught me how to build a racing bike from parts, enjoyed making sculptures and working with wood, built large parts of his house with his own hands, played the guitar, was interested in different cultures and always loved teaching. He was full of humor, great with our kids, strong and fit, all in all very lovable.

He always made me feel welcome in their lives. I never got the feeling he was judging me – he would have had every right to do so, since I married his daughter, but this absence of judgment made me feel like I was accepted by him. We spent holidays together, most Christmasses of course, and all major events like birthdays or other important days – for example, he came with us to Copenhagen to support me on my first IRONMAN triathlon, and during another IRONMAN he cycled to the bike route to greet me during the race. I couldn’t have asked for a better father-in-law. Always supportive, showing his helpfulness wherever he could. He read all the books I’ve written and most of my blog posts, where he often left a nice comment. Before he died, he left me one of his most cherished possessions, his self-built bicycle which has an original Hagen Wechsel welded steel frame. He cared.

So I decided to say goodbye by running a 75 kilometer ultra marathon in record time in his name.

One kilometer for each year he spent on Earth.

Coincidentally, this fit rather well, as our holiday home was about three kilometers removed from the coastline, so by running there and back again, the 68 kilometer loop would be extended to 74 – just one lap around the block left and that’s that.

Going unsupported.

This isn’t a symbolic decision but rather a competitive or practical one. The folks over at fastestknowntime.com have put down the rules for these attempts, and one of them is the categorization of runs into supported, self-supported, and unsupported. Here’s a short summary:

- Supported: A supported FKT (Fastest Known Time) attempt is a run with help from the outside. For example, have friends bring you water or food to the side of the road. Pacers helping you fight the fatigue and keep on track on long runs. Or even just people cheering you on. This is obviously the easiest category.

- Self-supported: Here, you do everything on your own, no help from the outside, except for the notable allowed option of buying stuff along the route. When you come by a little shop (or even a Burger restaurant, your choice), you can buy anything and restock your supplies as much as you want.

- Unsupported: This means that you do everything on your own, you can’t even buy anything during the run. You need to carry all the stuff you will need during the entirety, nobody is allowed to help you in any way. There’s one exception: water. You can’t buy it, but you are free to restock on water from all publicly accessible sources (not commercial ones), which can be little rivers or public water fountains or tabs. Asking at a shop for a free glass of water is not allowed, for example, because that’s outside help.

There’s no need to explain that the unsupported category is the hardest one and therefore beats the others. I saw that the current best of 6:33 hours was tagged as self-supported but I think that has been a mistake by the runners because in their description they did mention that they carried everything they needed.

I myself know that I can run for around 70 kilometers in the winter using only what my backpack holds, which is about three liters of water. In summer, the number depends largely on the exact temperature and other conditions like clouds and wind, but I estimated that 50 kilometers must be possible. Finding public water sources on the internet turned out to be nearly impossible – I found three on the whole island, but all of them far away from the track.

Which is why I made the decision to just go for it. Maybe I’ll find some conveniently located water tab or maybe I won’t – in which case I was sure I could find a camping ground store or something else which would sell me water, moving me one step down into the self-supported category. If that’s going to be the case, so be it.

Which direction to go?

With loop runs on fastestknowntime.com, the rule is that you’re allowed to start the run at any place of the route and run in either direction. The idea being, of course, that it won’t matter, because it’s a loop.

I contemplated this, because the wind would be my main enemy today. The island is flat but popular among wind surfers and kite surfers. Today, the wind would be coming from the northwestern direction, so I had to choose between having tailwinds during the first 20k and last 10k, headwinds during 20k to 60k, or the other way around, roughly. I went for the first option, because my thinking was that the last kilometers should be as easy as possible – having headwinds with that type of fatigue could be too disheartening. Was it the best choice?

6 AM, 14th of July, 2022. Start.

Except for the winds, the conditions were favorable. Not too much direct sun, but a warm and healthy temperature. Sunscreen was necessary. I had put my homemade sugar mix into one liter of the three liters of water I carried, took two CLIF bars and a handful of GU gels, and that’s it.

The first three kilometers acted as a type of warm-up. Running not much slower than a 5:00 min/km pace came easily, despite the still heavy backpack.

I thought about Peter a lot during this run and tried to run through his life, each kilometer representing a year. These first three years he spent in Loughborough, England. But then, right when I reached the coast, turned towards the East, and the official loop started, you could maybe say that his life really started, as well.

Because his family and him moved to Johannesburg at that time and this would become formative years for him.

Now, I don’t know much of his time down there, except that he went to a boarding school as per usual back then. Things were naturally different and tougher at the time, but he talked about a bunch of fun memories, too. He joined a cycling club and they even had a stadium for it – if you could call it that. From what Peter said, the cycling stadium had lifted curves, which is great, but the ground was just hard sand. Far from ideal for race cycling! Still, he spoke fondly of it. Maybe the tailwinds I was experiencing during the next 20k represented his years of adolescence in South Africa and Rhodesia.

I reached the southeastern-most tip of Fehmarn after 24 kilometers.

From then on, the headwinds started and the track turned into an overgrown single trail, which was quite a bit tougher to run, but the views were incredible and the feeling of freedom set in. There are cliffs to the side and you overlook a big part of the Baltic Sea. Peter came to Germany at age 26 to teach English – two kilometers after those more difficult but more enjoyable parts started. I saw a parallel there, as well. He was now an adult, got to experience the world, appreciate its possibilities, but also find some more challenges when compared to the time growing up, maybe.

He also met his wife, Susanne, at the time. I imagine them both looking into the future at the time, full of hope, together.

The beautiful cliffs ended and the route led down towards sea-level again. He spent a year in Leicester, England at around that part, but I know nothing about what happened there. I guess it had to do something with fully finishing his teacher training. In 1976, aged 29, he came back to Germany and found a position as a teacher in the small town of Otterndorf, an hour away from Hamburg. Coincidentally, I have done a bunch of triathlon races in that small village.

There were two small ports, Burgtiefe Yachthafen at 30, and Kommunalhafen at 32. At 30 years of age, Peter asked Susanne to marry him. At age 32, they did get married. I don’t know if that’s an English saying as well, but in German we say that we’re entering the port of marriage. A safe haven, a union to withstand the sometimes harsh conditions around us.

From age 32 to 53, Peter was a teacher of English and Geography at Gymnasium Meckelfeld. To me, he didn’t talk much about the time there, so I don’t know if he found it to be challenging or fulfilling – but probably a mixture of both. For me, these kilometers were the toughest of the run. I had to battle the starting fatigue, my water stash emptied fast, and the continuous headwinds required lots of willpower.

He son Neil was born when he was 35, and his daughter Sophie, my wife, at 39. That was the moment when I ran underneath the massive bridge connecting Fehmarn with the German mainland. Sophie, a bridge connecting me and Peter?

Up until this point, I have not come across any clearly visible public sources of water and started to make my peace with having to buy something soon and move out of the unsupported category. But then, right at 50, when I had just had the last few drops from my backpack, there was a public tab next to a marina, with a sign above it clearly stating that this is drinking water! How lucky am I. I’m not sure if Peter had such a lucky or maybe even life-changing experience at age 50, but then again this would be coincidental anyways. I’m doing this to remember Peter as best as I can and finding these parallels helps me do so.

I downed a full 500ml flask of water before refilling all three liters again, because I figured that the next 25 kilometers might not have any other public tabs to offer and the heat was certainly squeezing more water out of me now at noon than during the early morning.

At 51, there’s a short stretch of a few hundred meters which is totally unrunnable. The plants have grown so high and the track isn’t visible, so I need to carefully walk through it.

Again, I find another parallel. At 53 kilometers, I reached the lighthouse at the southwestern-most tip of the island and need to turn into a different direction now, North. At that age, Peter switched jobs after teaching at Meckelfeld for 21 years, to Immanuel Kant Gymnasium in the nearby neighborhood of Sinstorf.

Now the winds came sideways for me. That’s easier, but they also got stronger. The waves near the shore were violently crashing into the rocky beaches. Some of my slowest kilometers happened around here, I was spent. Calculating my time, it seemed to be near impossible now to beat the fastest known time of 6:33 hours. Mentally, I gave up that goal. Now it’s down to making it home in one piece.

Up until 58, my fight continued. I’m not sure what triggered it, but suddenly, some power awoke within me and I had access to some strength to get the pace up again. I like to think that Peter sent it.

The northeastern coast of Fehmarn draws a stretched out quarter of a circle, which meant that the direction of the wind would ever so slowly turn to my advantage. At 62, I had a great and very fast kilometer – that’s Peter’s age when Sophie and I met and he therefore entered my life, too. I love this parallel especially.

It’s like having him in my life slowly increased the amount of tailwinds I received over the years.

For him, it must have been similar. He retired early at 63 and was 64 when Sophie and I gave him his first little granddaughter. This must have started a period in his life which felt easier and much more joyous than before, maybe. Tailwinds. Over these years of retirement, some great journeys were had – especially one to Iceland made a big impression on him, and the amount of granddaughters moved up to five, total. Four from me, one from his son, my brother-in-law, Neil. I know this made him very happy.

With every kilometer the tailwinds and my pace increased. I made a conscious effort because I had calculated that the FKT would still be possible if I just ran as hard as possible now. Thinking about him during that phase of the run brought tears to my eyes (and now writing these words, too) – I felt like he was with me and gave me the strength.

The final kilometer of the loop was my fastest at 4:56 min/km and the watch proved that I did it. The 68 kilometers of the track were over after 6:29:39 hours, a new Fastest Known Time by four minutes. With some help from above.

The officials confirmed it. And here’s my Strava tracking.

But now, the hardest part begins. Running these last few kilometers back home, away from the coast. First, I bumped into my dad, sister, and their respective partners at a beach restaurant right next to the road leading home. Good timing, as they had just ordered beers and kindly offered them to me. That was perfect, I downed one and a half of them, thanked them a lot, earned some astonished giggles, and made my way towards the real finish.

As the 68 kilometers of the loop and the three of getting to the coast before added up to 71, I now had 4 kilometers left. I started running back home, very tired and with sore feet. This is the part of Peter’s life which was probably the hardest for him. At age 72, almost 73, he was diagnosed with ALS, a neurodegenerative disease, meaning that those nerves which control the muscles will slowly and steadily lose their function, resulting in the loss of muscle mass, and, after three to five years, death. There’s still no working therapy. You might recognize the disease because the well-known physicist Stephen Hawking had it. Or you might remember the Ice Bucket Challenge, which was created to gather funding for research because we still know almost nothing about the disease.

Peter’s muscles slowly went thinner. He was out of breath more often. It first showed when he asked me to carry his bags up some stairs during a vacation together because he suddenly seemed to not be able to do it himself anymore. A tough moment in the life of such an active person. At first, we thought this was just due to his age. It still took some months and many expert doctors to find and confirm Sophie’s suspicion of ALS (she’s brilliant at finding rare diseases in people, being a doctor herself).

After all which has happened during his last years on Earth, which unfortunately even coincided with the global pandemic and made it even harder for him, you can say that he was saved from a lot more suffering by his early demise while having the disease. About two and a half years after the first symptoms, now already significantly marked by the disease, he died on June 22nd of 2022, in his own home which he built, next to his wife who lovingly cared for him through it all.

His 75th birthday had just happened seven weeks prior. We were all there with him, but it was a sad occasion – he cried many times, had huge problems breathing and could barely even move. Even the mischievous kids couldn’t get a laugh out of him anymore, no matter how they tried. He was done, I think. Longing for release.

When I fell onto the garden lounger after these 75 kilometers for Peter’s 75 years, I felt it again, the connection. My daughter helped to put my legs on the lounger because I was totally spent, physically and emotionally.

But I felt content. This journey today, in remembrance of the life of my beloved father-in-law, Peter Huggett, represented closure for me. I’m not the guy who cries, but at his funeral and during this run, I did. And it was alright.

I am exceptionally thankful for having had such a wonderful person as my father-in-law.

Rest in peace, Peter. And thank you for everything. 🙏

How do you feel after reading this?

This helps me assess the quality of my writing and improve it.

Leave a Comment