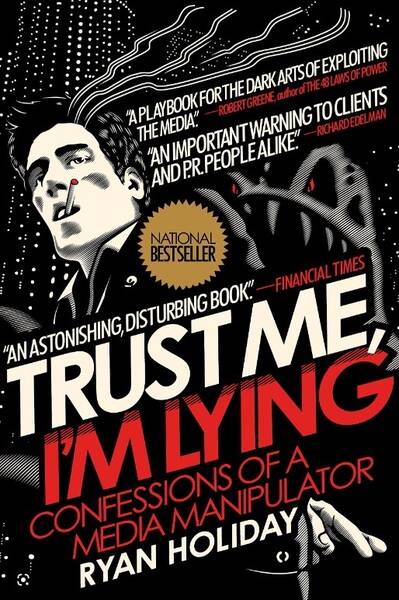

🚀 The Book in 3 Sentences

- The news is driven mainly by what might get the most clicks, and that’s strong negative emotions, regardless if the content is factual.

- Marketers abuse this mechanism to drive their agendas forward because the news industry is under constant pressure to publish a lot and publish fast, without fact-checking.

- This is highly problematic, because lies, amplified by the internet and disguised as outraged reporting have made it into what people think is facts and that has led to political polarization and extremism.

🎨 Impressions

This book is an angry confession. It’s worth noting that it was first published in 2012 and displayed all the mechanisms which were already in use at the time by people with certain interests to spread misinformation, or types of information which will serve their plans. Things like Donald Trump being able to become the president of the USA by using these tactics were plainly predicted.

Holiday later updated the book in order to explain in even better detail what happened to lead to such anger-driven and misinformed decision making in the general public. It is fascinating to read and understand what’s happening in the current news media, especially the strategy he calls “trading up the chain” in which an online marketer with an interest publishes a few blog posts under false names, tweets them with a few other false names and contacts certain reporters from news outlets with low standards until they publish the newly made-up information, which will then be taken from other, more sophisticated outlets, eventually make it into television and even Wikipedia due to its reliance on citations. Everything seems so easy to manipulate.

The whole book made me see the news in an even less appealing light – even the sources you thought you can trust are manipulated for getting the most clicks, because the incentives are aligned in that way. The disturbing fact is that you can’t really blame anyone for it unless you apply moral or ethical standards, but these need to be debated, too.

Holiday’s book is an important reminder of the situation we’re living in. We all have to take a real close look when an outrageous new fact is presented to us as a fact by any instance, if we should incorporate that fact into our own belief systems.

I’m following Ryan Holiday’s work, because since he stopped working in online marketing for the ethical reasons provided in this book, he moved towards something way more wholesome: promoting the ancient wisdom of Stoicism. That’s a lot less controversial and a lot more helpful to people.

🍀 How the Book Changed Me

- I had already reduced social media and news consumption to a minimum, but this book made me even more aware of its bad influence on the general public and our own mental health.

- Admittedly, I was intrigued to test out a few of the tactics of getting information beneficial to myself out there and noted by lots of people, but have since come to my senses and discarded that idea.

- The book made me think about what tactics are justifiable if they are used to promote helpful ideas to society more effectively – for example getting more people to understand climate change or public health.

📔 Highlights & Notes

Preface

“It’s difficult to get a man to understand something,” Upton Sinclair once said, “when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Introduction

Winston Churchill wrote of the appeasers of his age that “each one hopes that if he feeds the crocodile enough, the crocodile will eat him last.” I thought I could skip being devoured entirely. Maybe you did too. We thought we were in control. I was wrong. We all were wrong.

A good question about the ethics of a certain profession or activity is: What would the world look like if more people behaved like you?

Book One: Feeding the Monster: How Blogs Work

We’re a country governed by public opinion, and public opinion is largely governed by the press, so isn’t it critical to understand what governs the press?

If you get a blog on Wired.com to mention your start-up, you can smack “ ‘A revolutionary device’—Wired” on the box of your product just as surely as you could if Wired had put your CEO on the cover of the magazine.

According to the study, “the most powerful predictor of virality is how much anger an article evokes”

The problem is that facts are rarely clearly good or bad. They just are. The truth is often boring and complicated.

Things must be negative but not too negative. Hopelessness, despair—these drive us to do nothing. Pity, empathy—those drive us to do something, like get up from our computers to act.

It’s almost as if the insatiable media appetite for stories that will make people angry and outraged has created a market for anger and outrage.

As Brian Moylan, a former Gawker writer, once bragged, the key is to “get the whole story into the headline but leave out just enough that people will want to click.”

People don’t read one blog. They read a constant assortment of many blogs, and so there is little incentive to build trust.

Whereas subscriptions are about trust, single-use traffic is all immediacy and impulse—even if the news has to be distorted to trigger it.

The reason paid subscription (and RSS) was abandoned was because in a subscription economy the users are in control. In the one-off model, the competition might be more vicious, but it is on the terms of the publisher.

For some blog empires, the content-creation process is now a pageview-centric checklist that asks writers to think of everything except “Is what I am making any good?”

“We can’t hear how our style of writing is working unless we get responses—and if we’re bland, no one will answer.”

How to interpret lack of reaction to a blog? Warnock’s Dilemma, for its part, poses several interpretations: 1. The post is correct, well-written information that needs no follow-up commentary. There’s nothing more to say except “Yeah, what he said.”, 2. It’s nonsense and no one wants to waste time on it, 3. No one read it, 4. No one understood it, 5. No one cares.

The Huffington Post does not wish to be the definitive account of a story or inform people—since the reaction to that is simple satisfaction. Blogs deliberately do not want to help.

The Huffington Post Complete Guide to Blogging has a simple rule of thumb: Unless readers can see the end of your post coming around eight hundred words in, they’re going to stop.

Book Two: The Monster Attacks: What Blogs Mean

From the twisting of the facts to the creation of a nonexistent story to the merciless use of attention for profit—she does what I do, what any media manipulator attempting to monetize attention does.

They could never undo what they’d been accused of—no matter how spurious the accusation—they could only deny it. And denials don’t mean anything online.

The tactic has come to be called “concern trolling”—acting like you’re upset and offended in order to exploit the ethics and empathy of your opponent.

I want you to see where this kind of outrage manufacturing has left us. The manipulators are indistinguishable from the publishers and bloggers.

Breitbart was the first employee of the Drudge Report and a founding employee of the Huffington Post. He helped build the dominant conservative and liberal blogs. He wasn’t simply an ideologue; he was an expert on what spreads—a provocateur.

This is what opponents of the alt-right seem to miss. They are trying to make you upset. They want you to be irrationally angry—it’s how they win.

The only way to beat them is by controlling your reaction and letting them embarrass themselves, as they inevitably will.

That’s what web culture does to you. Psychologists call this the “narcotizing dysfunction,” when people come to mistake the busyness of the media with real knowledge, and confuse spending time consuming that with doing something.

Wikipedia administrators are not able to edit stories on other people’s websites, so the quote remained in the Guardian until they caught and corrected it too. The link economy is designed to confirm and support, not to question or correct.

The posts can be updated, they say; that’s the beauty of the internet. But as far as I know there is no technology that issues alerts to each trackback or every reader who has read a corrupted article, and there never will be.

Only 44 percent of users on Google News click through to read the actual article. Meaning: Nobody clicks links, even interesting ones.

Countless people fell for that—because they don’t actually click links. They just assume they know what’s behind them, and often they assume the links confirm whatever they want them to confirm.

Arthur Schopenhauer called newspapers “the second hand of history” but added that the hand was made of inferior metal and rarely working properly. He said that journalists were like little dogs: Something moves and they start barking.

Science essentially pits the scientists against each other, each looking to disprove the work of others. This process strips out falsehoods, mistakes, and errors. Journalism has no such culture.

Most social media experts have accepted this paradigm and teach it to their clients without questioning it: Give blogs special treatment or they’ll attack you.

Suppressing one’s instinct to interpret and speculate, until the totality of evidence arrives, is a skill that detectives and doctors train for years to develop. This is not something we regular humans are good at; in fact, we’re wired to do the opposite.

We place an inordinate amount of trust in things that have been written down. This comes from centuries of knowing that writing was expensive—that it was safe to assume that someone would rarely waste the resources to commit to paper something untrue.

My test is a little simpler: You know you’re dealing with snark when you attempt to respond to a comment and realize that there is nothing you can say.

You find it in nonsensical mock superlatives: Obama is the “compromiser in chief.” So-and-so is a perv. Jennifer Love Hewitt gains a few pounds and becomes Jennifer Love Chewitt. So-and-so is rapey.

To be called a douche or a bro or any such label is to be branded with all the characteristics of what society has decided to hate but can’t define.

Because you know who doesn’t mind snark or mockery? Who likes it? The answer is obvious: People with nothing to lose.

In fact, I don’t think it’s controversial to say that Trump thrives in our new media world in part because he, like some superbug that has become immune to antibiotics, transcends snark and criticism.

What if everyone did what you were doing? What would that world look like?

The news might be fake, but the decisions we make from it are not.

It’s a world where Trump becomes president by getting the media to repeat his dystopian paranoia and negativity enough times that people start to really believe that things are terrible—they substitute objective reality for the narrative they hear online and on TV.

Our facts aren’t facts; they are opinions dressed up like facts. Our opinions aren’t opinions; they are emotions that feel like opinions. Our information isn’t information; it’s just hastily assembled symbols.

Conclusion: So… Where to From Here?

Because your profession’s true purpose is to serve the best interests of your readers—doing anything else is to misread your own long-term interests. Advertisers pay you to get to readers, so screwing the readers is a bad idea.

When intelligent people read, they ask themselves a simple question: What do I plan to do with this information?

American Apparel is no longer in business. The strategies I talked about in this book were good for notoriety but ultimately mattered very little in the long term. Don’t forget that!

Leave a Comment