Personal Running Coach: Is it Worth Starting Your Running Training with One?

Have you been thinking about taking your running abilities to the next level? Maybe you’ve already tried a few training plans before, maybe not – but in any case, you’d like to make progress in order to get faster, stronger, or healthier? Best case scenario, all three of those things.

Will getting a personal coach make this process easier? And what’s the deal with that anyways? This post is about my experiment working with a coach and will answer some questions you might have.

First, a bit of my backstory. I have been on a quest to break the magical three hour barrier on the marathon distance for a few years now. Last year, I came very close once (3:00:40) and failed miserably the second time I tried. Both times, I trained myself using public training plans which I had modified to the best of my own knowledge about my body’s ability to improve.

After that fateful failed second try, I thought to myself: “I need help.”

Having been so close to reaching my goal, you would guess I did most things quite right already. And although I mostly knew what led to each of my two failures, I took into consideration that I might have overlooked something. And also, since I used training plans which were already a few years old, I got curious about what new methods the world of sports sciences has to offer, and if they might do the trick and get me under that three hour goal time more easily.

🔍 How to Find a Personal Trainer?

Since the relationship between you and your coach is usually quite close, I think it makes sense to get to know the person a bit before signing up. Personally, I was in a luxurious situation of having a few offers on the table from coaches in my circle, professional and hobby coaches both.

I think it’s because many of them followed my training and must have thought to themselves “What the $%&# is that idiot doing?!”

Be that as it may, this is obviously not a situation most other ambitious hobby runners find themselves in, getting to choose a coach. I would recommend asking around your running buddies, for sure someone has at some point heard of a coach or had one themselves – ask them how that went and decide if that approach would suit you.

But on what should you base that decision, apart from just a general liking of the person?

⚖️ What Do I Need to Look For in a Personal Trainer?

- Knowledge. This one goes without saying. Unfortunately, not everyone is as interested in keeping up to date, so there are signs to look for: Ask lots of “why” questions and listen if the responses make sense to you. Do they dismiss current developments in the training field right away? Bad sign. An experimental and curious mindset is what you should look for in a coach. Can they site sources for what they’re stating?

- Interest in you. It’s a coach’s job to take the trainee from where they currently are to where they want to be – this isn’t possible without trying to learn as much about the history and mindset of the trainee as possible. Does your coach care about what you’ve done so far and how your body reacts to different exercises? Do they listen carefully?

- Flexibility. Plans change, life gets in the way, individual training results differ greatly: A coach who wants to push you through a fixed plan from Day 1 to Race Day will lead you into certain disappointment and rapidly decrease your chances of success.

Don’t want to miss new stories?

Subscribe to the free newsletter here:

You’ll never ever receive spam email and you can unsubscribe at any point.

-

This was one of the best articles I've read so far in telling about a race. I couldn't put it down. Your details were so awesome. You made New York just come alive.

-

Great review, enjoyed reading it and recognize lots off related subjects and hurtles. I’m amazed by all your running and races well done.

-

Great article! I've read so many long blogs only to get bored in the middle as I suffer terribly from ADD and move on to other things. Yours has been one of few that held my attention all the way to the end.

-

Your good humor and ease in telling stories make this blog a really cool space. Nice review.

-

Amazing effort Tim, well done! Thank you for taking the time to write down your thoughts, feelings and memories from the event. There’s always something to learn from your posts and this one was no exception!! Another cracking read.

-

What a ride! Surely the race, but also reading about it. Thanks for taking the time to write up such a detailed report, almost feel like I was there.

For me personally, but I think this might apply to many others as well, a healthy balance between Humility and Conviction is another constructive quality. I want a coach to tell me what to do so I can outsource planning and thinking about that. The coach, therefore, has to be certain about their plans. But, and here’s the quality that I haven’t found in that many coaches, and that’s humility: A willingness to accept when the designed plan wasn’t perfect or led to undesired results. Trust in the process is important, but course-corrections are, too.

📜 My Own Journey With a Personal Trainer

The perfect combination of all those qualities was coincidentally offered by my running buddy Mathias.

He’s a professional consultant, a life-long teacher at heart, a stats nerd, and so much into sports sciences it’s scary sometimes. Also, he’s a good friend and is himself on a quest to slowly get to that 2:59h marathon some day. And, he was one of the guys watching my training sessions on Strava without being asked and unable to refrain from giving unsolicited advice to me. Which I, of course, appreciated. We all need all the help we can get.

🔀 How Did My Training Change When Working With Him?

First off all, I’m skeptical of those people who say that a specific new type of training regiment will yield much better outcomes for everyone. My argument is that the time tested ways of the past were successful as well, and I’m not here to break a world record. What worked for many runners of similar abilities to mine in the 1980s should be fine for me today as well.

But that doesn’t mean I’m not curious in the modern developments, especially after those two failures, regardless of the causes for those.

The conventional marathon training plan has for a long time included three weekly key training sessions:

- The Longrun: This is my favorite. Always has been. It’s usually done at a comfortable heart rate (think talking speed) and has to be of a certain duration to be effective. Opinions vary, but most would agree that fewer than 20 kilometers / 12 miles or less than two hours don’t count. A typical longrun for a finishing goal time of less than four hours should be between 30 and 35 kilometers (18 to 22 miles).

- The Intervals: In order to build the desired speed, interval runs have proven effective. This means, doing several short distance repeats at a significantly higher pace than race pace. In between fast intervals, use a slow recovery pace. Typical workouts would be 6x 800m or 4x 2.000m, on a running track if possible. The amount of repeats usually increases over the course of the training weeks. For a 2:59h marathon goal, a standard intervals session would be 6x 800m at a pace of 3:45 min/km or in less than 3:00 minutes per repeat. Recover for 400m. The cool thing here is that you can substitute minutes with hours of your marathon goal time and get the necessary 800m time, e.g. if you want to run a 3:30h marathon, do those 800m in 3:30 minutes each (4:22 min/km). Never forget to warm up and cool down to prevent injury.

- The Race Pace: In order to get accustomed to the desired goal pace, nearly all training plans involve some efforts at that pace. Near the end of the training cycle they occur more often. A typical session would be, warming up for 2 km, run at race pace for 15 km, cool down for 2 km. Those are intense, but get the body up to speed and build confidence as they get easier over the weeks due to improved fitness.

On the other days of the week, you typically would run easy shorter ones to get the weekly distance up. A training plan built on this is quite likely to succeed. But there are some other ideas these days, too. Mathias introduced me to a bunch of different variations which he had gotten from the world’s best endurance coaches, read all the studies, and was keen on trying them on me. Here’s the new stuff:

⛰️ Hill Repeats

It all began with so-called Hill Repeats. They sound dreadful and they are. I mean that. I love running, but hill repeats could only motivate me because apparently they make you stronger and faster quickly.

A typical session was divided into three sets of running slightly uphill seven times for 30 seconds as hard as you can, before turning around and jogging back down within 60 seconds. Three times seven is 21, so in total that’s 10.5 minutes of highly intense running with a heart rate near the maximum. To me, this felt a lot tougher than 800m intervals and therefore required lots of willpower.

I can’t really say if they did the trick, but the cool kids all do it.

🚲 HIIT on the Bike

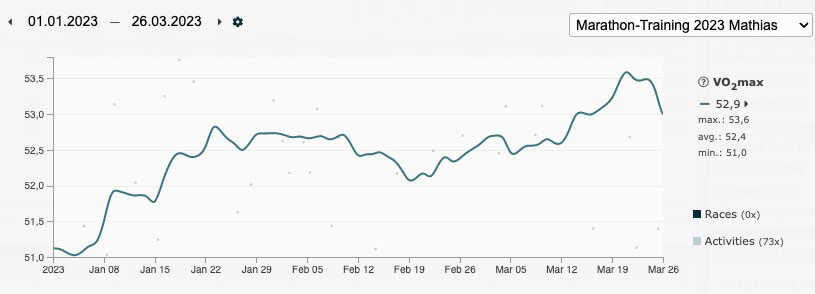

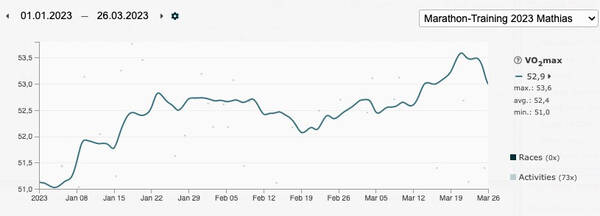

HIIT is High Intensity Interval Training. In order to build that VO2max level, which is the amount of oxygen your body can effectively utilize during exercise, cycling has become a valid option for runners.

The advantages include being able to do it at home on a bike trainer all through winter, having less of an impact on the joints, and causing nearly no injuries.

Old-school coaches usually say things like “If you want to run faster, you need to run faster!” – but there’s strong evidence suggesting that cycling harder will also make you run faster. There are several approaches to using cycling as a method of improving running fitness, but I think the HIIT is the most effective and most popular. It looks a lot like the Hill Repeats from before.

Three sets of 12 times 30 seconds at your upper limit, 20 seconds recovery. The recovery time is shorter because you don’t need to get back to the bottom of the hill for this to work. I liked these a lot better than I did the Hill Reps, although I felt similarly cooked afterwards every time.

⏱️ Switching From Distance to Duration

It’s a classic way to determine a session plan by stating the distance, as in 6x 800 meters or a longrun of 32 kilometers. But the amount of time you spend on your feet when running those distances naturally greatly varies depending on your speed. Which means that a faster runner might get less of a workout benefit from it, because the body adapts to the time you spend at a certain heart rate – it doesn’t care about the distance.

Also, if you’re getting faster over the course of the training cycle but stick to the same distances, you’ll get less of a workout relative to your previous ones each time.

This makes a lot of sense, but psychologically, I personally find it harder. When you know the goal to be a specific distance to cover (up until that lamp post, or around that lake), that’s easier to wrap your mind around than knowing you need to run for 120 minutes – you have no idea where you’ll end up. Also, those neat 800m intervals on a 400m track won’t line up perfectly anymore if you replace them with 3:00 minute efforts.

🎯 Race Pace All The Things

As stated, a weekly run at race pace can be found in most training plans. These are quite taxing, too, depending on your standing. To reach success, race pace runs don’t seem to be necessary, though. In fact, that training plan I used when I reached my personal best of 3:00:40 involved just two of those during the whole course of 14 weeks. (I mixed in a few additional kilometers during later runs on my own initiative, though.)

Mathias’ school of thought was different. He, and the countless studies he had consulted, advised for more race pace running. Even the longruns got some race pace treatment, similar to old-school hero Peter Greif’s thinking, but with a twist: Apparently it doesn’t matter that much at which point during your longrun you insert the race pace intervals, or, how long they are each. What matters is the total time spent running at race pace. So, in order to make it more easily digestible, you would do 5x 3 kilometers at race pace with 1 km of easy floating between those instead of the traditional 15 km tempo run in one piece.

And when you reach your peak fitness, a 5x 5 km race pace run automatically ends up being a longrun, including floats and warm-up / cool-down. Of course this also works when changed to 5x 20 minutes instead, but since the idea is to increase the amount of race pace kilometers each week, it doesn’t really matter if you use distance or duration – it’s relative to your previous effort.

😴 Rest Days

This seems to be a touchy subject among professionals. Some swear by it, some say it’s unhelpful. What I have heard quite often is something like this:

Make the easy days easy and the hard days hard.

It’s logical that it’s easier to run a tough intervals session after a day of resting. You’ll polarize you’re training that way, which will make it possible to train harder and simultaneously give your body time to adapt.

But, everyone is different. Some need the resting time, others don’t as much. Lifestyles differ. And since good recovery is so multi-factorial, it’s incredibly difficult to give general advice here. If you take a look at the professionals, some do rest days, some don’t. For me personally, I think rest days would help me get faster and fitter more quickly, but I’m not sure if the rest of my body would like that. And since I’m streak running every day for nearly 500 days now, there were no rest days for me, but I don’t think that hurt my progress significantly – quite the contrary. A slow 5k is very similar to a rest day to me. Or, speaking for world record holder Eliud Kipchoge, a slow 20k can even be like a rest day.

🍰 Getting Those Carbs

When running near so-called threshold pace, which is the exact point above which the running will turn from aerobic to anaerobic, meaning unsustainable for longer runs, the body does this most efficiently when fueled by carbohydrates as opposed to fats. It’s always a mix of both energy sources, and sometimes even muscle protein gets broken down by the body to provide energy. That’s what you don’t want to happen. The muscles should stay as they are and receive the amount of energy they need.

When going on a slow long run, your fat storage will last you for a long time because the heart rate isn’t as high, but at marathon pace, that’s different. Even and especially when it’s just in training as opposed to race day. Current research says that putting sugar into your body won’t affect or train your ability to “run fast on fat” significantly, so it won’t hurt.

This is among the things that I changed most when training with Mathias. And during those long runs including marathon pace, the sugar really made a huge difference. Having enough of it already on board going into the run is recommended, too.

Energy gels, which are the most common source of carbs for runners during high intensity efforts, are really expensive, unfortunately. And they mainly consist of sugar, so we started to experiment. I landed on Maple Syrup, the good Canadian kind. It’s cheap, has around 80% carbs in it, its consistency is easy to ingest, and I love the taste. I have a 150 ml soft flask which is perfect for carrying the stuff in my belt during a run.

[EDIT: Reader Philipp H. noticed that the difference between both products shown in the picture above is actually just ~2%, because the syrup on the left uses 100 grams as a basis, while the one on the right uses 100 milliliters. He put it all into Excel and came up with this result. So, it apparently doesn’t matter as much as I thought and either one will be full of useful carbs. Thanks Philipp! 🙏]

Maple Syrup is not everyone’s favorite, so Mathias’ own experiments resulted differently. He mixes isomaltulose with fructose and for taste he puts in ground-up freeze-dried raspberries. Cheap, tasty, effective.

🧑🔬 More Stuff to Try

Needless to say, when it comes to designing a training plan and its single sessions, there is no shortage of possibilities to try. The above ones are ones that Mathias put on my plan and which I did regularly, but there were even more. Among those are:

- The 5-5-5, which is a progressive 15 km run. The first 5 is done at Zone 2, which is a relaxed talking pace you also use during longruns usually, followed by Zone 3 for 5 km and Race Pace for another 5. For a 2:59h marathon goal, that would look like this: 5 km at 5:15 min/km, 5 km at 4:45 min/km, 5 km at 4:15 min/km. (8:27 min/mi, 7:39 min/mi, 6:50 min/mi)

- The Over/Unders, here, the sweet spot around which you will oscillate is again the goal race pace. A session for 4:15 min/km race pace could look like this: 7x 1 km at 4:05 min/km and 1 km at 4:25 min/km. I’m not quite sure what this is exactly supposed to do but it sounds fun and I’m sure I’ll try it too, one day.

- The Training Race, also a popular standard. Three to four weeks before the marathon, many runners like to enter a half marathon race and run that one to the best of their abilities at that stage, at an all-out effort. It’s fun, you’ll get a result to be proud of and which is a good indication of where you’re at, and if you multiply your finishing time by 2.1 you’ll get into the vicinity of what’s possible during the marathon race in a few weeks. It doesn’t have to be a race, you can also just pretend it’s one. And it could also be a full marathon, but that shouldn’t be done all-out, obviously. Rule of thumb is to do this at goal finishing time plus thirty minutes.

📓 My Subjective Experience

Training for an optimal marathon race is always a hunt for the sweet spot. You can set arbitrary goals like I did with that 2:59h time, but in the end your body decides how far it will let itself get pushed. I went into this personal training experiment with all my experience from previous training cycles and had lots of interesting and fruitful discussions about specifics with Mathias. That alone made me a better runner.

In the end, finding the perfect balance of hard sessions and recovery was more difficult than expected, though. Some sessions felt insanely hard but were digested just a few hours later, and some didn’t look too difficult on paper but punched me down with a vengeance. It was unpredictable to me and I learned a big lesson about listening more to my gut feelings.

One mistake I made was that I thought I could do more because I was already so close a year ago. My general fitness mostly stayed, but my speed and VO2max were down going into the 12 week training. I wanted to do too much too early. Mathias noticed and adapted the plan accordingly.

But a few weeks in, I caught a bad cold which struck me down for nearly a week. That was annoying, but could have been no danger to the goal. But then, just after getting back into it, two or three weeks later, it struck again and I was down doing very slow 3-5k runs once more. Part of the risk when having many small kids. I didn’t sleep well during those months, too, which additionally made recovery hard.

At that point I had nearly given up hope, but just nearly. I still saw a chance to run 2:59 at Hanover Marathon, end of March 2023. Completing my unlucky streak, I got sick a third time (!) just three days before the race. Seems like the stars just didn’t align in my favor this time, to no fault of Mathias at all. In the end I ran Hanover with a slight cough, almost recovered as a slow longrun and finished after 3:44 hours.

Getting sick this often is new to me and I’m positive that the training plan had nothing to do with it. The only thing I could learn from this specific experience is that life sometimes gets in the way so plans don’t work out and it’s no use to get angry at that.

🔁 What Will I Do Differently Next Time?

I think I might keep it simpler. The variation and all those modern ideas were fun but made it quite hectic, too. My feeling is that I might do better when I reduce the plan to the essentials and make them constant. For example, 800 meter intervals every Wednesday, 32 kilometer longrun every Saturday. I suppose that doing this consistently over the course of three or more months might get me there, too. And it leaves room for experiments whenever I feel like it, without screwing up too much of the training.

Despite all the sickness during those spring months, my speed definitely improved, and after Hanover Marathon ended up being a little longrun I had Boston Marathon coming up to test my fully healthy marathon running abilities. In harsh conditions on a difficult course I reached a finishing time of 3:22h, and just six days later I was able to run Hamburg Marathon and finish in just 3:14h. This shows that the training still worked quite well despite the sicknesses. A 2:59h marathon won’t happen for me this year, because I have different plans, but my next try in 2024 will hopefully be successful. At 80-82% of maximum heart rate and with enough carbs.

We’re all an experiment of 1. Let’s find out what happens!

How do you feel after reading this?

This helps me assess the quality of my writing and improve it.

Leave a Comment